To ensure a prosperous and financially secure future, we need to understand the potential roadblocks that can prevent us from succeeding. All too often, investors rush to implement a solution or buy an investment hoping that it will fill the gap created by previous portfolio hiccups, shortfalls, or downright mistakes. The desire to repair our immediate investment concerns may be quite valid; however, short-term adjustments usually do not result in any meaningful long-term impact. For winning strategies to work, investors must be aware of the pitfalls that await the unsuspecting. Knowing the rules of the playing field can save you a lot of headaches down the road—and dramatically improve your odds of future success.

While the eight common investment pitfalls discussed in this white paper are not new, they are now more relevant than ever. Investors are more likely to make knee-jerk decisions during periods of extreme volatility, which is precisely what we have endured since the financial crisis of 2008. Unfortunately, the data on investor response

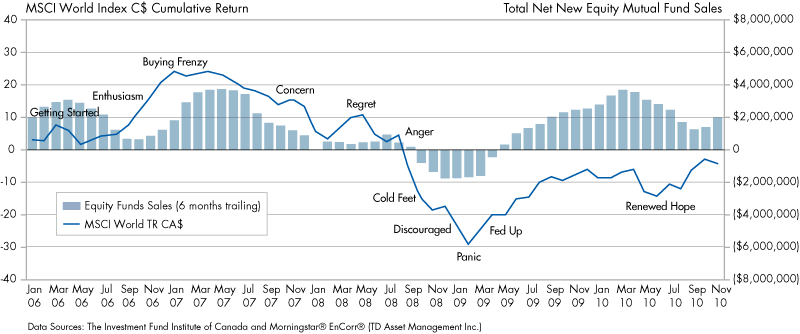

Figure 1: Buying High and Selling Low: An all too Common Reality

Investors reliably poured new money into equities after they had gone up in value and pulled money out of the markets after prices declined. In other words, they bought high and sold low with depressing consistency.

Errors like these are often caused by our emotional attachment to money. Family finances and investing stir up our most primal feelings of security and our desire to “make it” in life. Wrestling with these feelings while riding the rollercoaster of stock and bond returns may lead us to make portfolio decisions that we later regret.

Thanks to the new field of

What is the value of reviewing these common investing pitfalls? First, simply becoming aware of them can help you avoid the costly mistakes that plague many investors. It will also provide you with a foundation on which to base your understanding of the winning investment principles.

More experienced investors may feel they are already aware of these common mistakes. However, investors would be wise to review these eight pitfalls annually. Constant vigilance has tremendous value when it

Pitfall 1: Lack of an Investment Policy Statement (IPS)

The lack of a clear vision is the root cause of the majority of challenges faced by investors. Many people feel confused or apprehensive when it comes to their portfolio—and rightfully so. They’re bombarded with all kinds of information and they don’t know what it means for them. Investing is a daunting task and for many

- your long-term objectives

- your time horizon

- your saving and spending rates

- diversification decisions for your portfolio

- your tax consequences

- associated risks with your portfolio strategy

- rules of engagement for dealing with industry professionals

Think of these as landmarks that your IPS will help you navigate. By putting your plan in writing and linking it with your investment philosophy, you create a blueprint for your investments that will help guide you along the path to achieving your goals. A good IPS highlights how all the moving parts work together and elaborates on the decision-making process used to execute the investment philosophy for you and your family. Why is it important to have an investment plan? We work with plans when we build our homes or cottages; successful entrepreneurs and business owners have a vision and a plan; companies and organizations have them as well; so too should our investments.

The world of investing is always changing, but a well-constructed and disciplined plan will allow you to be well positioned during good times and bad. Instead of worrying about the challenges presented in the short term, a sound investment plan will help you become better informed about the relationship between returns, risk, and time horizons. It will shift the focus to the proper management of your long-term portfolio. By prioritizing the long-term health of your investments, you’ll be better positioned to weather challenges and common pitfalls in the short term. An IPS is a key component of investment success.

Pitfall 2: Lack of an Investment Philosophy

An investment philosophy (also called investment strategy) is a set of guiding principles that shape and inform an individual’s, an advisor’s, or an advisory firm’s investment decision-making process. While an IPS can be thought of as a map, your investment philosophy is a code of conduct that defines how your money will be managed. The investment philosophy is the star by which you steer; it is the approach you take when it comes to managing your money.

Your investment philosophy determines how you behave as an investor. There’s an old adage that says, “If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.” Without a clear belief system to govern how you invest, you risk falling into the other pitfalls on this list.

Investors who are frustrated or confused about their portfolio, or are having a hard time understanding the big picture, often either don’t

Pitfall 3: Being Unaware of the Mathematics of Sustainable Portfolios

Canadians remain unaware of or unable to appreciate the significance of the mathematics of sustainability, despite the fact that numbers don’t lie. Sustainability means taking proper care of our resources so that we may continue to use them in the future. In financial terms, it means setting aside enough money for financial independence and a fiscally healthy retirement. Most of us are not doing this.

In 1989, Canadians were introduced to David Chilton’s The Wealthy Barber, which suggests investing a percentage of what you earn in long-term growth. Be it 10%, 15%, or 20% (perhaps even 30% if you have neglected your savings), you should set aside an annual percentage of your earnings for your retirement. The amount you save affects how much you will be able to draw down after you retire. Sustainable portfolio drawdowns must be used throughout retirement. For 60-, 65-, and 70-year-olds who want to have thirty years of inflation-protected retirement funding, prudent and conservative amounts to withdraw each year are 3%, 4%, and 5%, respectively. However, many Canadians reach the age of retirement with the impression that they can draw down 10%, 15%, or even 20% of their portfolios. Once again, this is a case of people misunderstanding or simply being unaware of the mathematics of financially sustainable portfolios.

Sustainability is the key word when it comes to planning for retirement. Ask yourself, “Is the life I live now going to be sustainable in the future?” The answer should always be a resounding “yes.” Today’s challenge, unfortunately, is that you almost need to be an actuary in order to appreciate the consequences that arise from not living a sustainable lifestyle. At a bare minimum, Canadians need to become aware of the math involved in a sustainable lifestyle and the factors that affect its outcome. We are seeing the effects this lack of sustainability has had

By not adhering to a sustainable financial lifestyle, investors often fall into the trap of looking for solutions that will recover the ground they’ve lost due to their lack of necessary savings. This emotional reaction causes investors to have unreasonable expectations of their investments and costs them in the long run. Instead of staying the course laid out by their IPS (assuming they have one), the desire to remedy their lack of savings and ensure their retirement

It is impossible to overstate the importance of understanding the mathematics of sustainability.

Pitfall 4: Trying to Profit by Timing the Market

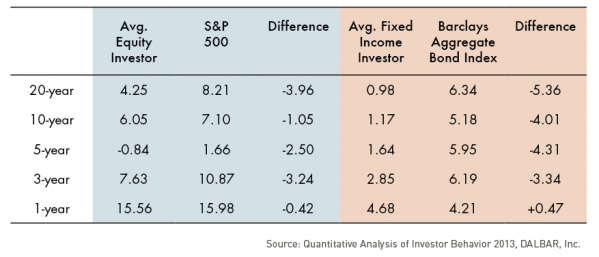

A classic study of American investors by Dalbar—one of North America’s leading financial services research firms—clearly shows the negative effects of trying to time the market. Dalbar tracked monthly cash flows in and out of mutual funds from 1993 through 2012 and came to the following dismal conclusions: over the last twenty years, the average U.S. equity fund investor earned 4.25% annually, falling far short of the 8.21% the S&P 500 earned over that period; the average bond fund investor earned 0.98% annually, compared with the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index return of 6.34%.

Table 1 shows the 1-, 3-, 5-, 10-, and 20-year annualized returns for the average equity and fixed income investor in the U.S. When comparing these annualized returns to corresponding benchmarks, we see both equity and fixed income mutual fund investors underperforming the market in nearly every time frame.

Table 1: Annualized Fund Investors Return vs. Benchmark

Current world events or media frenzy, rather than future economic reality, can drive panicked investors to sell. Whether caused by 9/11, the financial crisis of 2008, or the ongoing debt problems in Europe, anxiety spurs investors into wild selling sprees. Dalbar’s 2013 survey revealed that investors continue to make these same mistakes. The fear generated by negative headlines or a lackluster earnings report prompts investors to deviate from their plan and sell their assets. They then miss the recoveries that inevitably follow and buy back in only after prices have increased. Countless studies and reports have proven that you are better off staying in the market throughout the good times and the bad.

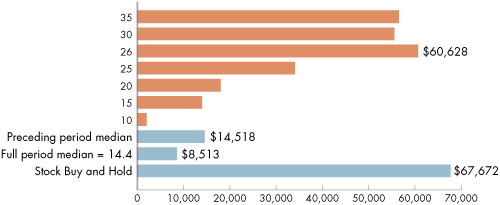

Market timing is not always about emotions: some people insist that they can use charts and other indicators to determine the best times to get in or out of the market. In an article in the Journal of Financial Research, Larry L. Fisher and Meir Statman analyzed various market- timing models that try to determine when the market is “expensive” and should be sold, or “inexpensive” and should be bought. Figure 2 shows that the “Stock Buy and Hold” approach would have provided the highest growth of assets compared to timing the market based on P/E trading rules.

Figure 2: Timing Isn’t Everything

Pitfall 5: Chasing Performance

Have you ever bought a stock that looked like a superstar only to watch it fall by 30% before unloading it? The equity markets are filled with buyers and sellers who act on emotion and respond to media hype. The cold, hard truth of the matter is that investors who do not separate themselves from their emotions will

Buying individual stocks at their highs and chasing after hot fund managers and asset class performance are not new phenomena. When we make the initial purchase, we undoubtedly feel that we have a good reason.

Investors buying at high levels in industries such as technology, pharmaceuticals, banking, real estate, consumer retail, and commodities have all landed in hot water during the last twenty-five years or so. While these sectors should all be part of a long-term portfolio, trying to determine which one will be the next hot performer is not the ticket to untold riches.

Pitfall 6: Lack of Proper Diversification

Most investors know that it is prudent to diversify, but do they truly practice diversification in their portfolios? Many people who believe they are well diversified actually have highly-concentrated and risky portfolios. The lack of proper diversification (by asset class, industrial sector, geographic region, and currency) ranks as one of the most serious investment pitfalls, and it exposes many people to potentially large losses. Many investors and some advisors don’t seem to fully appreciate and understand this concept. They believe owning fifteen stocks or ten mutual funds makes them diversified. But too much overlap results in bad diversification, which can be costly in the long term. It is not the number of stocks alone that provides diversity, but the variety.

Why do investors forego the benefits of diversification? One reason is that over-confident investors believe they have the knowledge or skill to identify which sectors or asset classes will be the best performers in the near future. To these people, diversifying their portfolios would be admitting that they are too timid or too ignorant to make bold moves;

For other investors, the problem is simply a lack of awareness of the difference between good and bad diversification. They might feel that they are enjoying the benefits of diversification because they have many mutual funds (or many advisors); however, if the funds or investments have overlapping exposure to certain industries, their portfolios may be highly ineffective.

While, on occasion, highly-concentrated portfolios can lead to significant gains, the lack of proper diversification exposes investors to potential losses that may be just as large—or larger. All too often, investors only consider the upside and ignore the downside.

Proper diversification also protects you from unexpected events. The term “black swan” comes from the ancient misconception that all swans were white—it was originally used as a metaphor for something that did not exist. When black swans were discovered in Australia in the seventeenth century, the term took on a new meaning: it describes something that is considered impossible until it actually comes to pass. In his book The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb extends the metaphor to the financial world. He explains that a black swan is a market event that is unpredictable and has a massive impact. More importantly, Taleb says, we concoct an explanation after the fact to make the event appear less random and more predictable than it actually was. In the financial world, the astonishing success of Google was a black swan; 9/11 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 were black swans as well.

Black swan events can have profound effects on a concentrated portfolio, but their impact can be mitigated by diversifying your exposure to risk. You cannot prepare for specific black swans: by definition, they are unpredictable. However, by remaining broadly diversified, you can ensure that your portfolio will not be devastated by any single event.

Pitfall 7: Building Portfolios Based on “Expert” Predictions

It is important to understand and accept that the financial industry depends on predictions to build its value propositions. Wall Street, Bay Street, the brokerage industry, and the financial advisory business have used slick marketing campaigns to position themselves as experts at predicting the markets. These predictions usually appear in the form of stock tips, market analyses, or mutual fund reports. How useful is this “expert” information? The evidence clearly shows that the accuracy of these predictions is hit and miss. Yet poor track records do not stop so-called investment gurus and financial market pundits from coming up with ever more elaborate scenarios with increasing certainty. They’re the white noise of the investment world and you will be much better off once you tune them out.

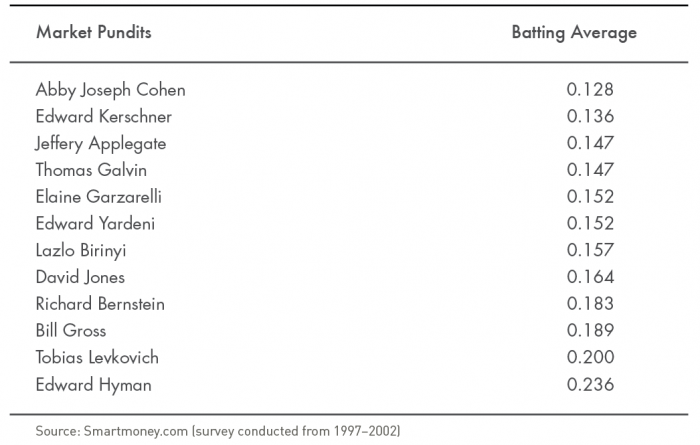

Just how far off the mark are these predictions? SmartMoney.com tracked the forecasts of Wall Street equity market strategists during the bull and bear markets

Table 2: Stock Market Gurus – Consistently Unreliable

In hindsight, this six-year survey period offered market strategists a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to predict market movements that included a major surge followed by a historic meltdown. Not one of them was able to predict these major events.

The accuracy of market predictions has not improved in recent years. The most telling example involves the predictions (and lack thereof) made prior to the market crash of 2008. Not only did the industry fail to anticipate one of the biggest financial crises in history, many market strategists failed to predict the ensuing market rebound that took place following the collapse. And while market predictions at the end of 2011 warned us of the implosion of the bond market, the collapse of the

Why are investment predictions so often wrong? There are several key reasons. For one, it is impossible to correctly predict the movement of an asset class without predicting the numerous factors that influence asset prices. Therefore, to predict asset class prices, strategists also need to be able to accurately predict the following:

The financial industry wants you to believe that it can successfully predict future market outcomes; many investors eagerly buy into this notion, often with dangerous results. The truth is that no one can predict future asset prices. Making major portfolio bets on these predictions is one of the most dangerous things an investor can do.

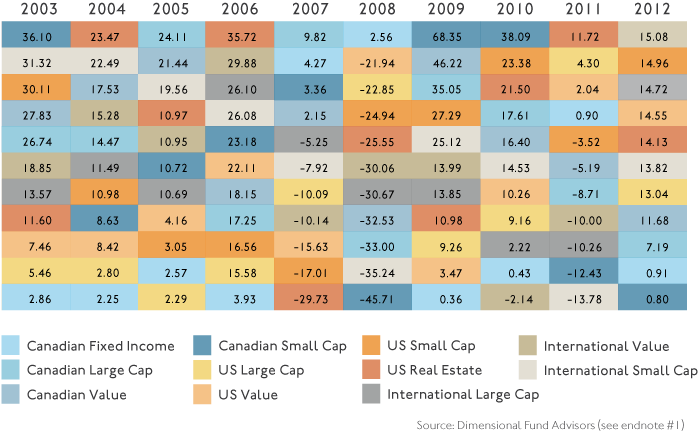

The truth of the matter is that no one can consistently predict future asset prices. As seen in figure 3, markets and asset classes often move in a random and unpredictable fashion. Each

Figure 3: Don’t Try to Predict the Unpredictable

Annual Asset Class Ranking:

Figure 5: Don’t Try to Predict the Unpredictable Annual Asset Class Ranking:

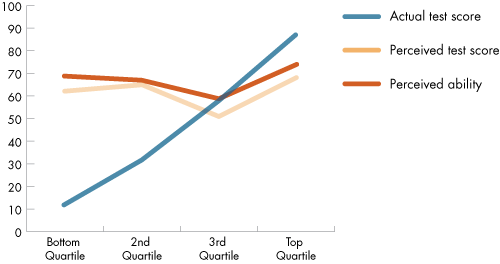

Investors should also be wary of market gurus who make their predictions with unshakable confidence. David Dunning and other researchers have documented a troubling pattern: individuals who rank among the worst predictors tend to be the ones who have the most confidence in their abilities.

To test this troubling pattern, Dunning and his colleague Justin Kruger asked people to rate how they performed on a logic and reasoning test. Figure 4 splits the different ratings for perceived ability, perceived score, and actual score into the four quartiles based on performance. Remarkably, those who did not perform well still had very high levels of confidence in their perceived abilities. It’s no wonder that we can get into difficulties by listening to market forecasters.

Figure 4: Unskilled and unaware of it

In truth, no one has the ability to consistently forecast important geopolitical and economic outcomes—there are no crystal balls. With catchphrases like “Ten Stocks to Buy Now” and “How to Retire Rich,” the advice business has largely succeeded in convincing investors that it has the inside track. Predicting an uncertain future has become the bread and butter of many in the financial services industry, and the public has been all too willing to buy into it. In the short term, setting the entire direction of your portfolio on the basis of a few predictions may lead to joy or misery; in the long term, it might lead to much less than you’d hoped for—not to mention encouraging you to become that Nervous Nelly investor you never wanted to be.

Pitfall 8: Letting Behavioural Biases Get in the Way

Humans are not hardwired to be great investors. Emotions such as fear and greed often cloud our judgment and lead us to do things with our portfolios that we later regret. Our brains also have a set of filters—or thinking biases—that can lead us to make less than rational investment decisions.

Successful investors are aware of the impact emotions can have on portfolio decisions. Warren Buffett writes: “Success in investing doesn’t correlate with I.Q. … Once you have ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.” Unfortunately, few investors have Buffett’s unflappable temperament. For the rest of us, money is an emotional subject, and the choices we make in the wake of an exciting stock tip or a plummeting portfolio affect our investment results in real and often damaging ways.

So powerful and insightful are the findings from

Some of the more common cognitive errors include:

- being driven by a desire to be part of the crowd or by an assumption that the majority knows best.

- treating some money (such as gambling winnings or an unexpected bonus) differently than other money.

- making decisions based on the information most readily available rather than considering all relevant information.

- a tendency to make decisions designed to avoid losses rather than to achieve gains.

- the belief that a recent unexpected event could have been foreseen (“of course a financial crisis was going to occur in 2008—it was obvious”), which provides subconscious support to the belief that we can predict future outcomes.

- the tendency to look for evidence and research that confirms our investment beliefs, while disregarding evidence and research that does not.

- the belief that investing in our own country is less risky because it is more familiar.

overconfidence is the opposite of fear of loss and can be just as devastating to an investment portfolio.

This

Empower Yourself—Become Aware

Awareness pays off. Financial markets have been extremely challenging in the last decade and the 2008–2009 financial crisis was just the latest sharp edge that rattled investors into succumbing to one or more of the pitfalls. It is important for investors to learn from their past mistakes and focus on obtaining the best possible returns available to them. Investors must:

- become aware of pitfalls that can endanger their long-term investment success;

- educate themselves on capital markets and how they work, the relationship between risk and return, and the strategies to avoid common mistakes;

- build investment plans using time-tested strategies based on diversification and long-term asset allocation; and

execute and maintain their chosen investment plan with discipline.

It’s time for a different kind of investment strategy—one that allows investors to pursue their dreams without endangering their livelihoods. Education and awareness enable investors to see beyond